History of Wu Yi Yan Cha

One of the most famous stories associated with Yan Cha is the legend of Da Hong Pao, or "Great Red Robe." The story tells the tale of a student who was on his way to the national exam and got sick in Wu Yi Shan. He took shelter at the current Tian Xin Yong Le Temple. The monks in the temple nourished him back to health to continue to the capital for the national exam. The student eventually won first place in the national exam, which immediately placed him among the nation's top elites. When he went back to the temple to thank the monks, he wore a red robe to show his new status. The monks told him that the teas they gave him from the back of the temple revived him. To show his gratitude, the student went to the tea trees, took off his red robe, and put it over them.

This tribute gave those tea trees fame and the name Da Hong Pao, Great Red Robe. This story is so well known, the name "Da Hong Pao" is widespread but mistakenly used synonymously with Yan Cha. As popular as this story is and the many variations, there's minimal record indicating its truth other than the story's main character. Ding Xian's student did exist, and the temple is still significant in the area.

Nevertheless, Wu Yi tea does have a very long history of being a tribute tea, and since the Tang Dynasty (618 AD – 907 AD), people have been raving about tea produced in the region. But, similar to the other historically famous teas, we cannot definitively conclude that in those times, Wu Yi tea was made in the same style as Yan Cha today. It is more likely that the tea made in the region before the late Ming Dynasty (1368 AD – 1644 AD) was green tea, and it was not until the abolition of certain restrictions on tribute teas that Yan Cha as we now know it was first created.

Yan Cha Geography

One of the most defining factors contributing to Yan Cha's unique mouthfeel is the very rocky terrain called Danxia Landform, where the teas are grown. Like all historically famous teas in China, the specifics of the locations are meticulously detailed. Zheng Yan, which translates to True Cliff, refers to the core part of the Wu Yi Shan.

Famous Yan Cha (Cliff Tea) Regions

This core is centered around the ancient Hui Yuan Temple and extends north to Lotus Peak and south to Jiu Qu Xi (Nine-turn Brook), roughly 18 square miles. Due to the popularity of Yan Cha, the True Cliff region has slowly been "expanding" in the past decade, but the most desired lots are still marked by the tiny area surrounding Three Pits and Two Creeks.

The Three Pits:

- Niu Lan Keng (Cow Fence Pit)

- Hui Yuan Keng (Wisdom Garden Pit)

- Dao Shui Keng (Opposite Water Pit)

The Two Creeks:

- Liu Xiang Jian (Flowy Fragrance Creek)

- Wu Yuan Jian (Spring of Enlightenment Creek)

Other Prominent Zheng Yan

- Jiu Long Ke (Nine Dragon Dwelling) Where Da Hong Pao is

- San Yang Feng (Three Up Peak) the highest peak

- Tian Xin Yan (Heavenly Heart Rock)

- Xiang Bi Yan (Elephant Trunk Rock)

- Zhu Ke (Bamboo Dwelling)

- Gui Dong (Ghost Cave)

- Mao Tou Yan (Horse Head Rock)

Half Cliff Region

Ban Yan, or Half Cliff, refers to the immediate area surrounding the Zheng Yan area: imagine a more extensive, concentric circle of land around the core that is Zheng Yan. Unlike the Zheng Yan region, where the varietals of tea trees are stable and limited, in Ban Yan, one finds more tea varietals and more affordable Yan Cha. Ban Yan teas are also significantly more fragrant than Zheng Yan's but have less body and are short on the "rock bone" characteristic. The well-known Ban Yan locations are Huang Bai, Xing Cun, Xiao Wu Yi.

Tong Mu Region

About two hours outside of the core Wu Yi Shan area is the world-famous high mountain area called Tong Mu. Even though it is a region most famously known for producing the world's oldest red tea (what the West knows as black tea), Zheng Shan Xiao Zhong (Lapsang Souchong), it is also a Yan Cha producing region. Often referred to as Gao Shan (High Mountain), the Yan Cha from this region sells for similar prices as Ban Yan teas. It is significantly sweeter and softer than the cliff region teas but lacking the highly sought-after Yan Yun rock chime, which Yan Cha connoisseurs pay for. Well-known Gao Shan Yan Cha villages are Xi Yuan, Wu San Di. However, the majority of Yan Cha we see on the market are Zhou Cha, a word locals use to describe the plantation teas in the region. Wu Yi Shan is a popular tourist destination for its stunning natural beauty, and many Zhou Cha are sold to tourists seeking the famous Da Hong Pao.

Yan Cha Processing

Like all Wu Long (Oolong), Yan Cha picks only leaves, making it one of the latest teas in the season every year, with Ban Yan picks time around early to mid-April and Zheng Yan early May. The most elementary way to tell if tea is Zheng Yan or not is by the time the finished tea comes out: the roasted Zheng Yan loose leaf tea does not come out until August or September.

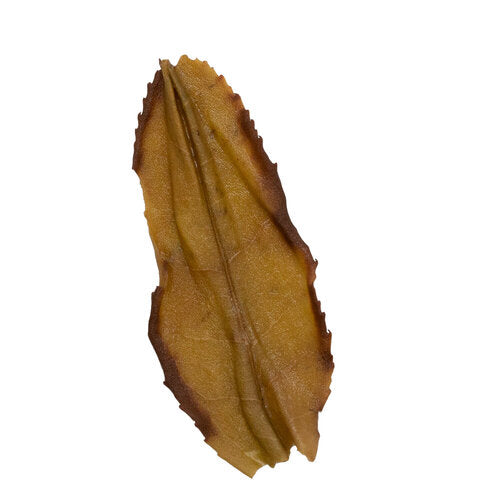

Yan Cha picking consists of roughly 3-4 leaves with stems.

The picked teas then are spread out under the sun to wilt until soft (according to hand feel). After the teas are sufficiently wilted, they remain on bamboo trays for a few hours before being shaken or tumbled to regulate how the water inside the leaves travels out, thus managing enzyme activity in the leaves. This process is repeated every hour, 5-8 times throughout the evening and night until morning.

Once the teas are acceptably fermented in the early morning, they are then wok-fried to kill the enzymes in the leaves to stop the fermentation. Fresh out of the wok when the leaves are still hot and soft, they are rolled vigorously to break the surface membranes to bring out more consistent flavors in the tea.

After the rolling of the leaves, they are evenly spread out and baked a couple of times to dry. This process gives us mao cha or rough tea. The most tedious step in all Chinese tea making is the stem-picking step, which in Yan Cha's case takes place for several months following the rough tea making. It is a step where undesired yellow leaves (old leaves) and stems are removed. The "cleaned" tea gets roasted on very dim charcoal ash for 8–12 hours, 1-3 times depending on the varietal, to make it a finished Yan Cha. Locals call this step stewing. The traditional method of making Yan Cha is very dependent on the weather at the time of the making. In general, it is tough to make good tea on rainy days. Feeding charcoal heat to tea resting in a tumbling machine is a standard modern-day remedy to counter undesirable weather. Zheng Yan village holds the annual Dou Cha Sai or tea competition.

The categories are: Rou Gui, Shui Xian, Da Hong Pao (blended contest), Ming Cong / Pin Zhong