What is Green Tea?

By definition, green tea is not fermented. However, enzymes metabolize naturally as soon as the leaves are picked, and a micro amount of fermentation is unavoidable. After the leaves are harvested from the trees, they are left sitting under shade for a few hours to let the surface moisture evaporate. They treat the best green tea leaves very carefully to avoid bruising or damage during this process.

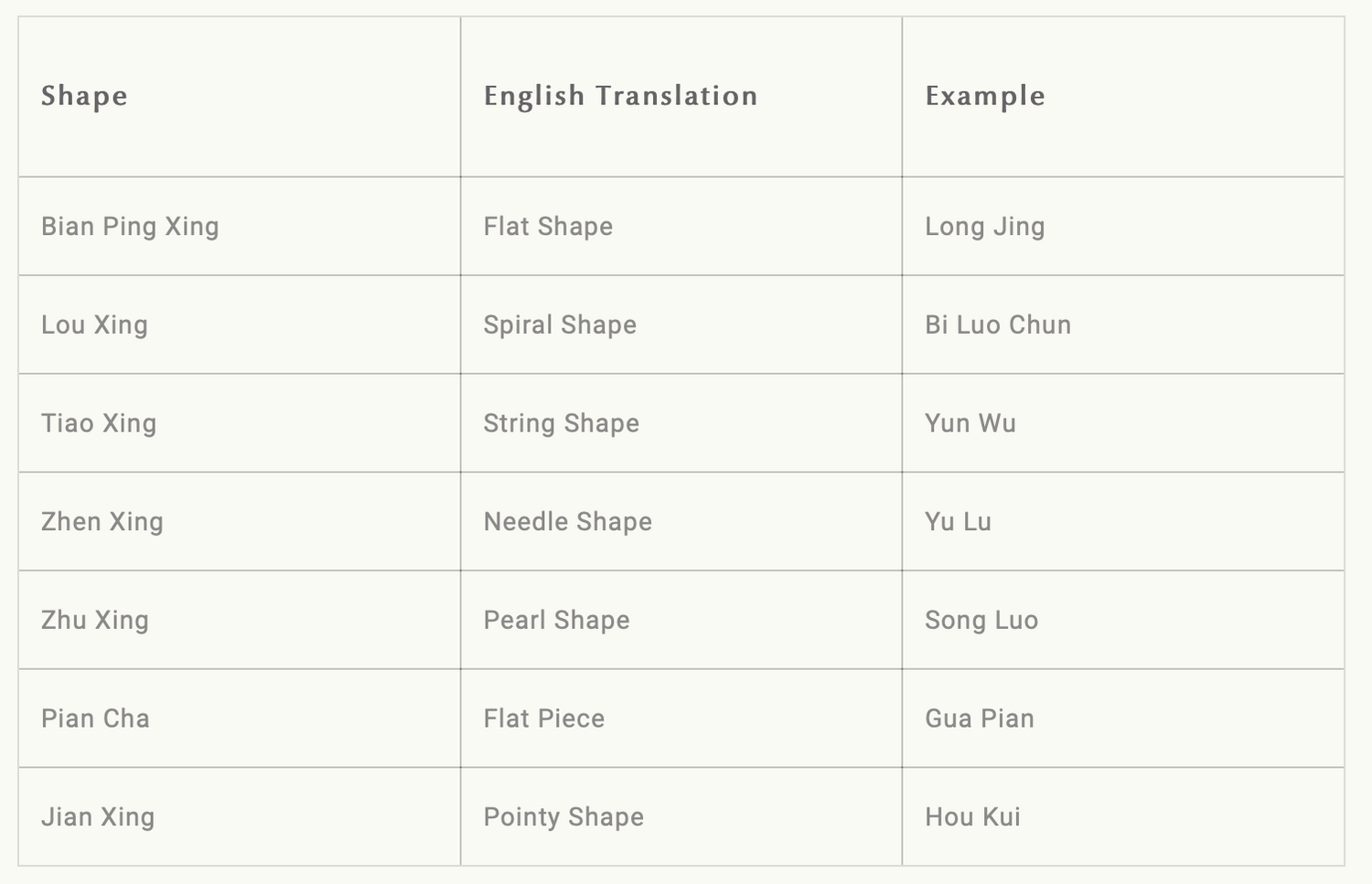

Then, the freshly picked leaves are treated with high heat to kill the enzymes present, preserving the tea in its freshest state. All this hard work retains most of the green tea leaves' original properties and taste and is the most astringent category. Based on processing style, there are four sub-categories of green tea.

The Four Sub-Catgeories

Picking Grades

The most common picking styles of green tea are one bud and one leaf or one bud and two leaves. However, picking time during the season is a significant factor in the quality and price of the resulting loose leaf tea. The cooler the microclimate is for the tea region, the later the tea season starts, making the loose leaf tea is more desirable than in warmer areas.

However, this is not to be confused with a late-picked loose leaf tea because higher-quality tea is picked early (but not too early) during its growth cycle.

What is Qing Ming?

Qing Ming is one of the 24 points on the Chinese farming calendar that fall between April 4th and April 6th, depending on the year. The point is commonly understood as the cut-off date for harvesting the most prized green teas, with the picking grade regarded as pre-Qing Ming or Ming-Qian. The date is only relevant to teas produced in the Jiang Su and Zhe Jiang tea regions and is not an absolute parameter for judging the tea's picking quality. Chinese ancient wisdom suggests that it usually rains on Qing Ming.

After the rain, the temperature rises, and the tea tree's buds grow much faster, therefore lacking the necessary time for the leaves to develop their complexity. This environmental change is why people are interested in the picking date. Leaves in warmer climates also tend to establish rougher tannins, which give the tea a harsher mouth feel and more bitterness. Because the northern tea regions of China have varying temperatures, Qing Ming doesn't apply to many well-known green teas such as Gua Pian, Yun Wu, etc., but the same core concepts still apply.

Green Tea Varietals

Other than the location (which is fundamentally essential for achieving the desired microclimate) and the picking time, a key factor contributing to the resulting tea is the varietal. Different varietals bud at different times, and late budding varietals are more desired than earlier ones.

Although the greatest chance to encounter the traditional technique and indigenous varieties are in the green tea regions, as a category, green teas are also the most "infested" with clone varietals for increased yield and stability.

Old varieties bud late and offer more complex flavor, while new varietals bud much earlier by design, with a one-dimensional flavor profile.

One of the greatest myths in green tea is that the earlier the tea is produced, the better the tea is. The truth is, many earlier picked teas are clone varietals from plantations, likely with the assistance of fertilizer.

Season Dates:

- Long Jing: March 23 - April 10

- Bi Luo Chun: March 27 - April 10

- Mao Feng: April 3 - 20

- Gua Pian: April 12 - May 1

- Yun Wu: April 12 - May 5

- Hou Kui: April 15 - May 1

Famous Chinese Green Teas

-

Xi Hu Long Jing (Dragon Well)

Since the Qing Dynasty, no tea has enjoyed fame comparable to Long Jing. Often regarded as the King Tea of China, knock-offs of this famous tea are so common that most of the Long Jing sold on the market is fake. Because Long Jing was regarded highly by generations of tea connoisseurs, its desired locations have long been ranked. The true origin of Long Jing is Xi Hu or West Lake. Within Xi Hu, the ranking goes Shi (Lion), Long (Dragon), Yun (Cloud), Hu (Tiger), Mei (Plum). Long Jing is strong, but unlike the sharpness of Bi Luo Chun, Long Jing is blunt. A textbook description of Long Jing's flavor profile is roasted chestnuts. While nuttiness is a prominent flavor trait of Long Jing, well-made Long Jing also has floral notes with plenty of refined tannins.

-

Lu An Gua Pian

Contemporary tea from a historical tea region, Gua Pian, is still made with impressive ancient techniques and picking style, making it one of the most distinctive teas of China. Being the only green tea with only leaves and no stems nor buds, Gua Pian is surprisingly not astringent. The unique La Da Huo (Puling the Big Fire) step offers the tea a pleasant toasty flavor that compliments its grassy umami taste and bold sugary undertone. The indigenous varieties of Gua Pian are humbly called Ben Cha (stupid tea) by locals and buds much later than the clone of the varietals; they are virtually two different tea seasons.

-

Xin Yang Mao Jian

Mao Jian is the name - referring to the pointy shape - of a baked dry green tea. While there are many Mao Jian among Chinese teas, the most well-known are Xin Yang Mao Jian and Du Yun Mao Jian. Due to the location's relatively north latitude, Xin Yang Mao Jian's prime harvesting time is in the second half of April. Xin Yang Mao Jian also goes through a vigorous rolling process to make the shape tight and pointy, making it more robust than other bake dry green teas. Though in He Nan Province, these tea mountains are still part of the Da Bie Mountain range, giving it similar thick and sugary undertones with Lu An Gua Pian and Huo Shan Huang Ya. Che Yun Shan (chariot cloud mountain) is one of the top 10 terroirs for this tea. Che Yun Shan is also where He Nan and Hu Bei border, home of two villages with the same name, both named after the mountain and two different provinces. The He Nan side (Xin Yang) demands higher prices on the market.

-

Lu Shan Yun Wu

Yun Wu means cloud and fog. Grown in one of the coldest and cloudiest tea regions among all teas, Fog Tea is an appropriate name for Yun Wu. In the old days, there was a saying that tea loves Yin, not Yang, and there's no tea region we have visited that is more Yin than Lu Shan. Yun Wu originates from this scenic mountain, with the top micro-lot being Xiao Tian Chi with over 3000 feet in elevation. It is exceptionally foggy year-round and at all times throughout the day, not just in the mornings. For a tea region that is relatively north, this elevation is impressive – that tea can survive this extreme climate is a miracle. Lu Shan Yun Wu remains one of China's "tribute" teas, with selected batches reserved for high officials and visiting diplomats. Well-made Yun Wu is savory and floral, with lingering flower notes and sweetness. Its showy profile grants it passionate likings and aversions.

-

Huang Shan Mao Feng

Huang Shan is one of the most magnificently beautiful mountains globally, and its tea has long been among China's best. Though we can trace the history of Huang Shan tea as far back as around 1050 AD, it's not until the 1500's that it gained popularity and fame. Huang Shan tea at the time was called Huang Shan Yun Wu. There's a time gap between the Huang Shan Yun Wu and this Huang Shan Mao Feng. Still, due to the defined location of Huang Shan, Mao Feng is generally viewed as the continuation of the celebrated Yun Wu (which is not to be confused with Lu Shan Yun Wu). Unlike most of China's traditional teas, where there's a shape-making step during the making, Mao Feng is "freestyle." The leaves naturally curl up to a "bird tongue" shape due to the high temperature, making Mao Feng one of the hardiest and fluffiest green teas. Mao Feng is also quite savory. It's one of the mildest green teas with an almost unusual tenderness for its category. The earlier the picking is, the lighter the dry leaves' color and liquor are. The buds are significantly smaller in earlier picks (more desired) and curl more naturally due to higher moisture content.

-

Dong Ting Bi Luo Chun

Small and tender, but delivering one of the sharpest tastes in green tea, Bi Luo Chun does not taste as delicate as the leaves look. Bi Luo Chun has a warm and fuzzy mouthfeel from its hairy buds, with notes of toasted rice and flowers. Bi Luo Chun is very tender. To receive the teas' signature spiral shape, the leaves are heavily hand-rubbed during the making process. Because of this, makers use a green tea brewing method called Shang Tou (top-down). We place the tea leaves into the water on the first brew instead of pouring water over the leaves. A well-made Bi Luo Chun should sink to the bottom right away. An early spring Bi Luo Chun is expected to clog the strainer with tea hair.

-

Tai Ping Huo Kui

With a leaf length of over 70mm, Hou Kui is the largest green tea. It is made using a big-leaf varietal called Shi Da, highly unusual for a green tea. There is no tea more tedious to make than Hou Kui. Every leaf of this tea is individually hand pressed, and if you look closely, you can see the pattern of the fabric in the leaves! Hou Kui is grassier and significantly more floral than the other green teas. Many people become fans of this tea for its umami and fresh taste and its elegant dance in the glass. The true origin of Hou Kui is Tai Ping country, with Hou Keng (Monkey Dip) hailed as the top terroir. Other notable terroirs include Lu Xi Keng, Yan Jia Lu, Hou Gang, and San Men Ling. Hou Kui is one of China's latest harvested green teas due to colder climate and shape requirements. It is usually harvested end of April over ten days. The genuine Hou Kui is always darker than the machine-flattened Hou Kui, which is light green and harvested using empty buds.